I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you’ve actually left them. Somebody should make a song about that.

Andy Bernard in The Office

I’ve been travelling quite a bit in the last 6 months—Santa Barbara, Austin, Lisbon—talking to people in the general NeuroAI orbit. If there’s one word to describe the vibe I’ve found, the zeitgeist of this period, it’s febrility: a nervous excitement. On the one hand, it’s hard not to fall into existential dread about AI1. On the other hand, AI actually works, and it feels like we’re in an age of discovery: anywhere you look at in the brain, you can apply some novel perspective from machine learning and understand a little better what makes us human.

I’m enjoying the latest book from

, The World Behind the World2. It’s a book about how people have thought about consciousness through the ages, leading into modern consciousness research. He emphasizes that consciousness research is in a pre-paradigmatic phase in the Kuhnian sense: disorganized, with constant debate over fundamentals, with as many theorists as there are theories.I would argue that NeuroAI is in a slightly different position: it is peri-paradigmatic. It’s not quite a free-for-all, and there are paradigms which are well-accepted. In particular, the paradigm of task-driven neural networks, put forward by people like Dan Yamins, Jim DiCarlo and Niko Kriegeskorte has a well-established core paradigm. It has a long pre-history dating back to the 80s from the Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP) group; successful efforts at formalization from people like Alex Williams; and vibrant and successful applications in human neuroscience from people like Talia Konkle.

On the other hand, some parts of NeuroAI are far less mature. What would a NeuroAI model of the frontal cortex look like? Or for that matter, of consciousness? It might require an entirely different paradigm than the ones we have been using elsewhere.

How do you define something as you’re going along?

The NSF has funded a new center of excellence at Columbia for NeuroAI. With that comes some resources to build a course through Neuromatch Academy (NMA). I’m super excited that NMA can help build that following its successful courses in computational neuroscience, artificial intelligence and climate change.

But it is challenging as NeuroAI is significantly less mature than these disciplines. To create a course in NeuroAI, especially a reference course that might be taken by hundreds of students, we have to go through an effort of systematization. It would be a missed opportunity to create a course that takes a highly idiosyncratic view of NeuroAI and runs with it: it would be exclusionary and potentially limiting for the field.

Strong viewpoints considered harmful

In the absence of one globally accepted paradigm, I think we will have to take a more synthetic view that accommodates several viewpoints. Here’s one line of divide:

The primary arrow of influence in NeuroAI is and should be Neuro → AI. We should take inspiration from the brain to build more capable machines.

Versus the opposite view:

The primary arrow of influence in Neuro is and should be AI → Neuro. We should look to new techniques in AI to help us understand the most mysterious object in the universe, the brain

I’m personally on team AI → Neuro, as I’ve made clear before. There are many routes to that argument, including:

The hardware of the brain is different than the hardware of AI. You probably won’t learn much of anything that will be transferable from neuro to AI because a lot of the architecture is idiosyncratic to brain hardware.

Neuro is hard: experiments take years. AI is comparatively easy: experiments take days. It’s just much easier to make progress in silico.

AI is growing exponentially. Neuroscience isn’t. It’s normal that opportunities should flow from a rapidly growing field to an established one.

So, hypothetically, if I was to make Patrick’s course on NeuroAI, it would be focused on AI → Neuro. But I don’t think that would be the right call for the NMA course. Because I can think of a fourth reason why I’m on team AI → Neuro: I know that field very well. I got into that field because I found it aesthetically pleasing. Because of that impetus, I became an expert in that field. The papers that fall on my desk that take that viewpoint are familiar and readable. The papers that take the opposite viewpoint are weird and foreign.

Schismogenesis in NeuroAI

This self-awareness really came together for me when I read The Dawn of Everything from David Graeber and David Wengrow [excellent review by Erik Hoel]. They describe the process of schismogenesis, wherein two people, located side-by-side, in similar environments, end up adopting wildly different societal organizations: say, communism on one side, and capitalism on the other. The Davids applies to the study of the wide range of societal organizations in pre-contact America, including close to home in the valley of the St-Lawrence river: from the peaceful Huron, immortalized in the figure of Kondiaronk, a brilliant orator and chief who popularized what later became the Rousseauian notion of the noble savage; to the Iroquois, who engaged in vicious wars against their neighbours, including the Huron.

The model is very simple: people with very similar but ever so slightly different initial conditions come to occupy different niches through the engraining of small competitive advantages. These competitive advantages cause the selection of environments and customs suited to these advantages, which further engrains them. Pretty soon they come to define themselves in contradistinction to each other. This is a powerful model of politics, not just in pre-contact America but in modern times: from the two solitudes of Canada to the red state/blue state divide in the US. It may well be a mathematical reality, a special instance of a general process of symmetry-breaking that operates at multiple levels, from the electroweak transition in physics to the creation of multiple parallel visual streams from similar hardware in NeuroAI.

Analysis by synthesis

I eventually came around to the viewpoint that the neuro → AI route was equally interesting. I saw some people, including Dan Yamins, Talia Konkle, Yann LeCun and Stéphane Deny, make contributions to self-supervised learning based on ideas partially inspired by the brain. I saw some very cool work using brain-inspired methods to actuate a worm (!). I heard Jitendra Malik make a cogent argument that we should look to neuroscience for potential solutions to problems in robotics.

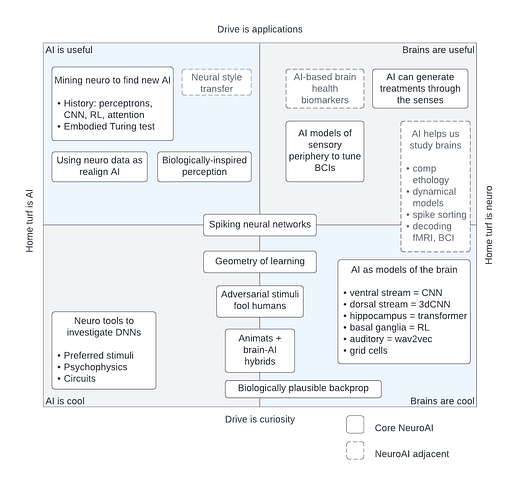

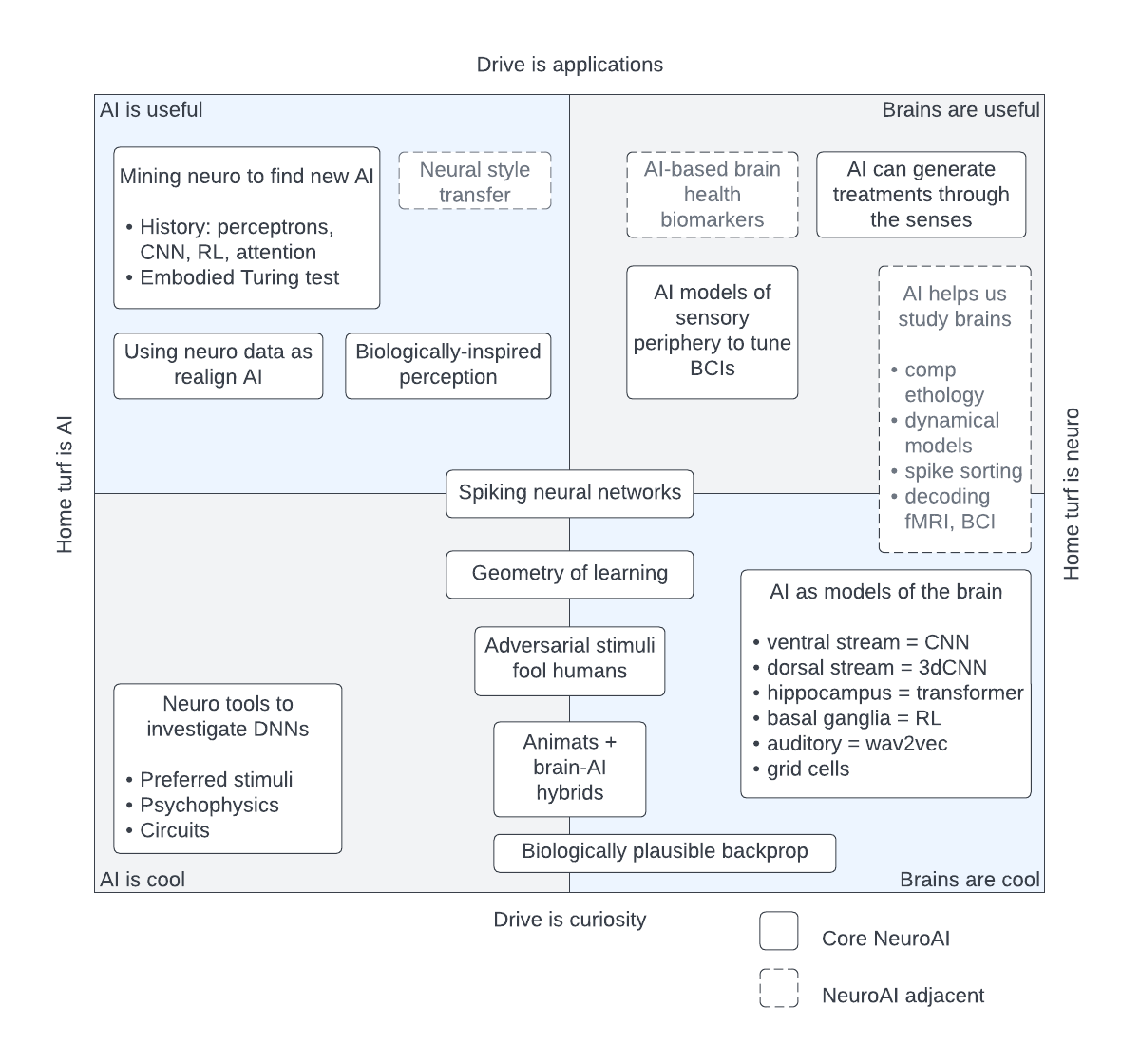

Finally, I did my own research: with the assistance of an LLM, I trawled over 40,000 articles published in machine learning conferences over the last 40 years. I found over 1,500 papers that took ideas from neuroscience to AI and vice-versa. There’s a lot of diversity in the range of investigations that people take in NeuroAI, and a lot of them are not things you would necessarily think of at first glance when you ask yourself “what is NeuroAI?”.

Strength through diversity

NeuroAI is more diverse than the image any one investigator can hold in their head. To teach NeuroAI is to teach the breadth of approaches that people take. Nothing is fun for the whole family; design by committee is often lack of design. But I think in this case it is unavoidable that it should take a wide viewpoint: to be relevant and representative, this NeuroAI course should be an overview of the different viewpoints of NeuroAI, not a deep dive into a particular one.

How can we avoid the trap of trying to be all things to all people, thus creating a slog of a course? First, we should define our audience carefully: should it be for neuroscientists? For AI people? Second, we should carefully establish a common trunk corresponding to the tools of the trade: mathematical foundations in linear algebra, Bayesian statistics, and deep learning.

Through this process, we will build a careful basis upon which to define our field, one that goes beyond the idiosyncratic aesthetic preferences of a handful of researchers.

though some people are trying to counter that

light criticism, he uses the term “intrinsic perspective” far too often, and as a French speaker who subvocalizes, it feels like I’m reading a book of tongue twisters